How and why will EVs be the main vehicles in the future?

Just like the internet and then the smartphone, electric cars will soon be a mainstream product that most of us never had and yet in the course of our lives changed everything beyond recognition.

This revolution is being accelerated not just by the natural growth of technology but also the grave danger that faces humanity and nature: namely global warming and climate change. Humanity’s back is against the wall. Which in reality is a great motivator and innovator.

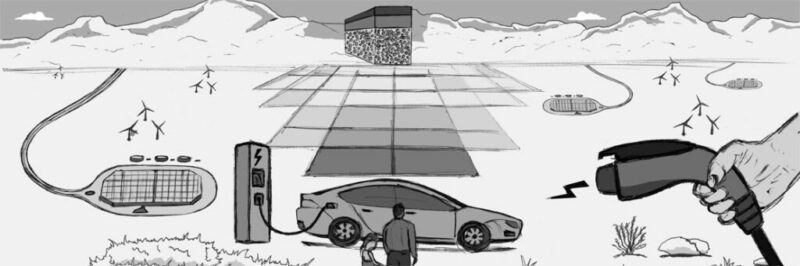

Within transportation cars are the biggest source of greenhouse gases and electrifying them will go a long way towards halting the destruction to the thin layer of atmosphere that separates us from the dark void of space. Fuel cell EVs that use hydrogen as the fuel source instead of a battery are also another option that could make headway. We have no choice but to give up fossil fuels – and fast.

Even if the electricity grids that power electric cars are fed by fossil fuels this is still better for the environment as EVs are more efficient at converting energy to power in addition to being emission free. They are cheaper, cleaner and perfectly adequate for home charging and the local area. Until longer lasting solid state batteries arrive on the scene and the charging networks have been fully built, the worry about having enough range to reach one’s destination will remain an issue but with good planning this can be avoided.

Automakers are scrambling for position in the new gold rush, eager to capture positions of dominance in this new industry. Tesla has been the leading innovator so far with the manic genius of Elon Musk at the helm, but others are close behind including established German automakers and one of the richest tech titans on the planet: Apple.

So far ‘halo vehicles’ like those from Tesla have been built for wealthy early adopters but ultimately products for the mainstream consumer will need to be mass produced. Gigafactories providing thousands of new jobs are being built on different continents to manufacture the powerful batteries needed to drive this revolution forward to achieve a zero-carbon future. Resembling gargantuan battery packs lying flat on the landscape, with access roads coming off them like attached cables, these huge factories manufacture not only batteries but the electric motors that make up part of an EV.

But all this comes at a price and as always there are winners and losers. The natural environment is being poisoned and destroyed in the hunt for the lithium and cobalt metals needed to make the essential batteries come to life. As production ramps up remote communities will be starved of their local drinking water, needed in huge quantities in the bright yellow and green lithium evaporation ponds covering the landscape in Chile’s Atacama salt flat.

Even this is only the beginning, just a trickle before demand for EVs turns into a raging torrent. Can the earth keep up with the demand? For even these metals are finite and non-renewable. Alternatives will have to be found and research is already underway.